“I like to say, ‘Okay, you’re going to see this. This is going to conk you over the head when you see it. And, God forbid it should fall off the wall, it would probably kill you.’”– Renee Cox reflecting on the Bad Girls exhibition at New Museum in 1994

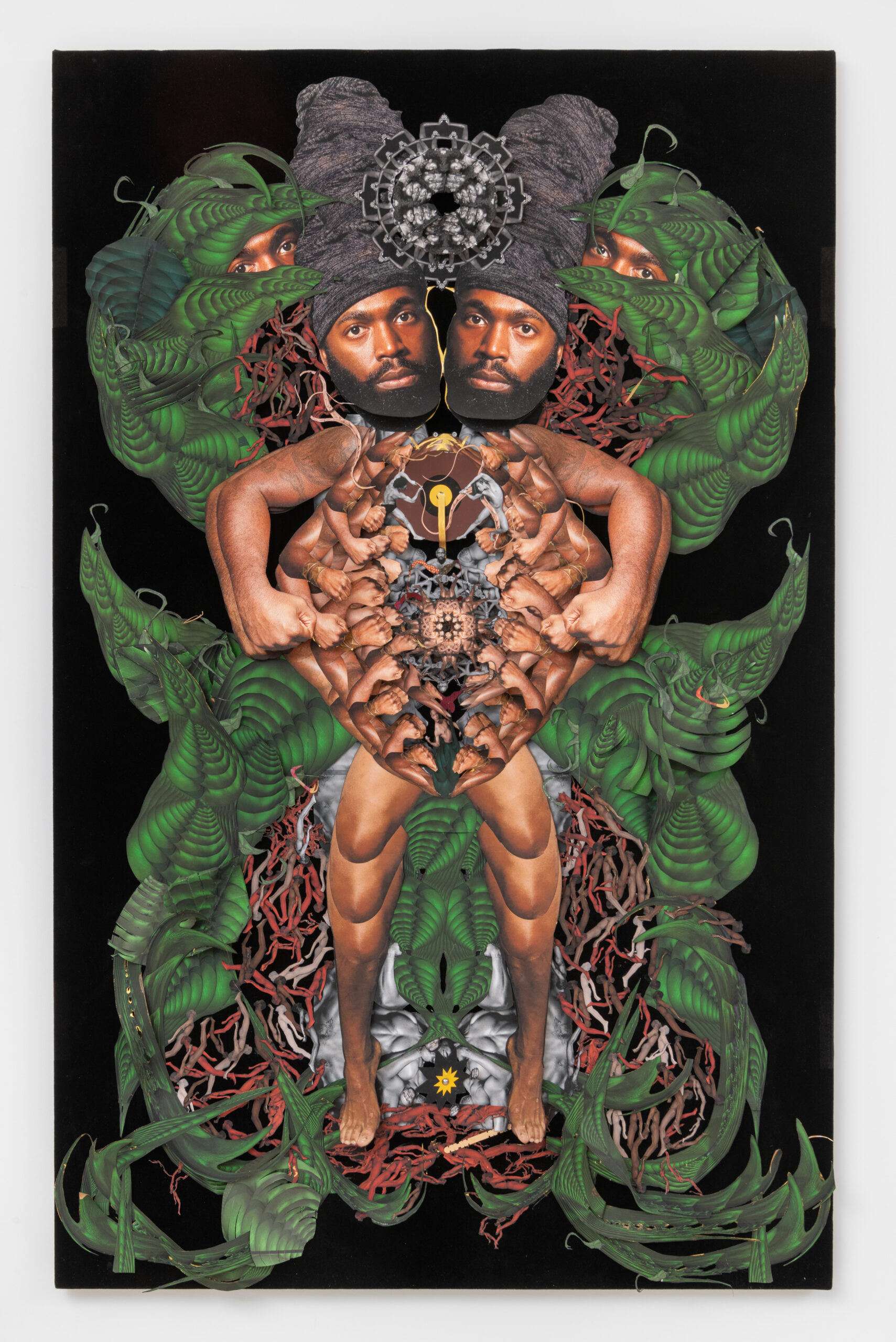

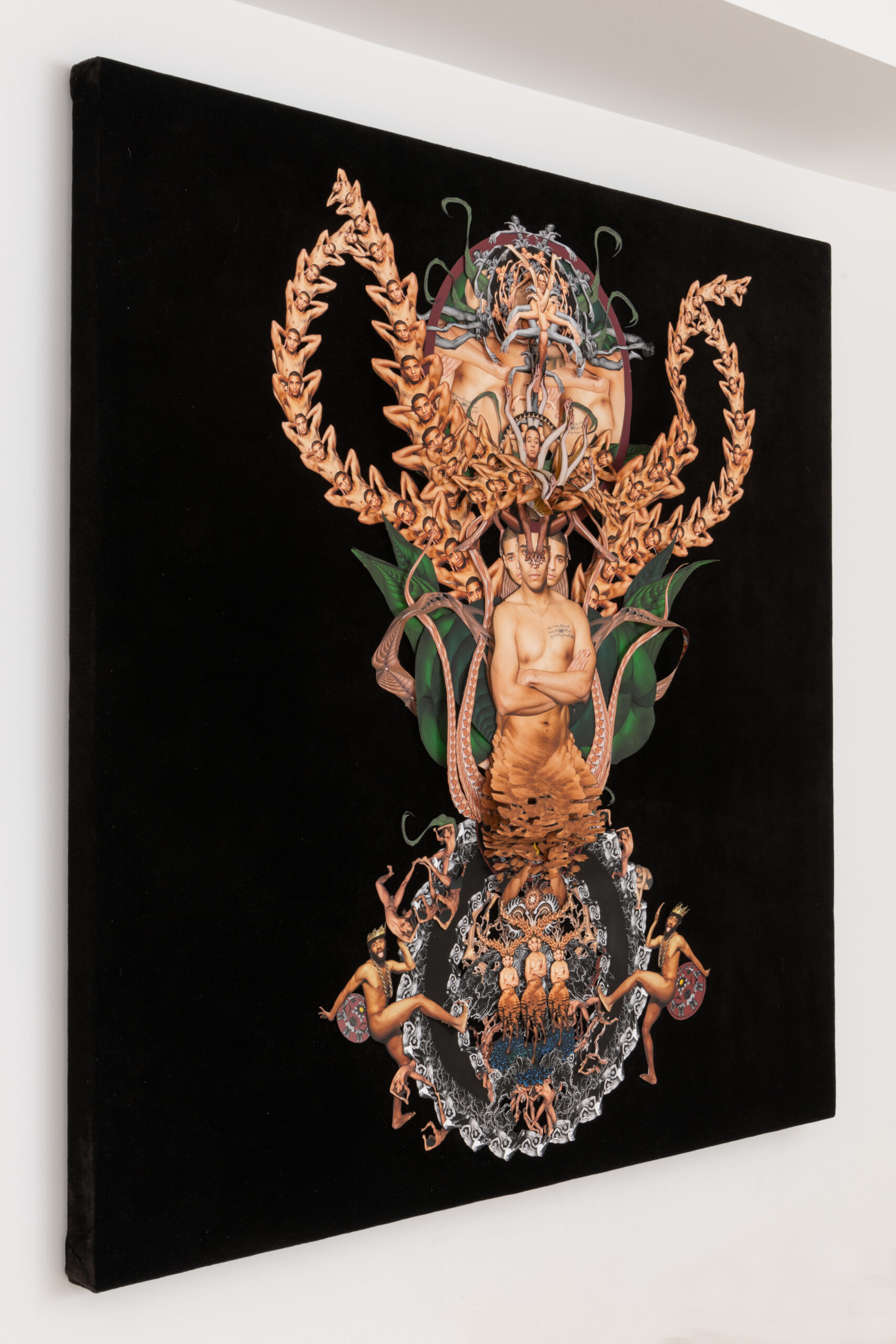

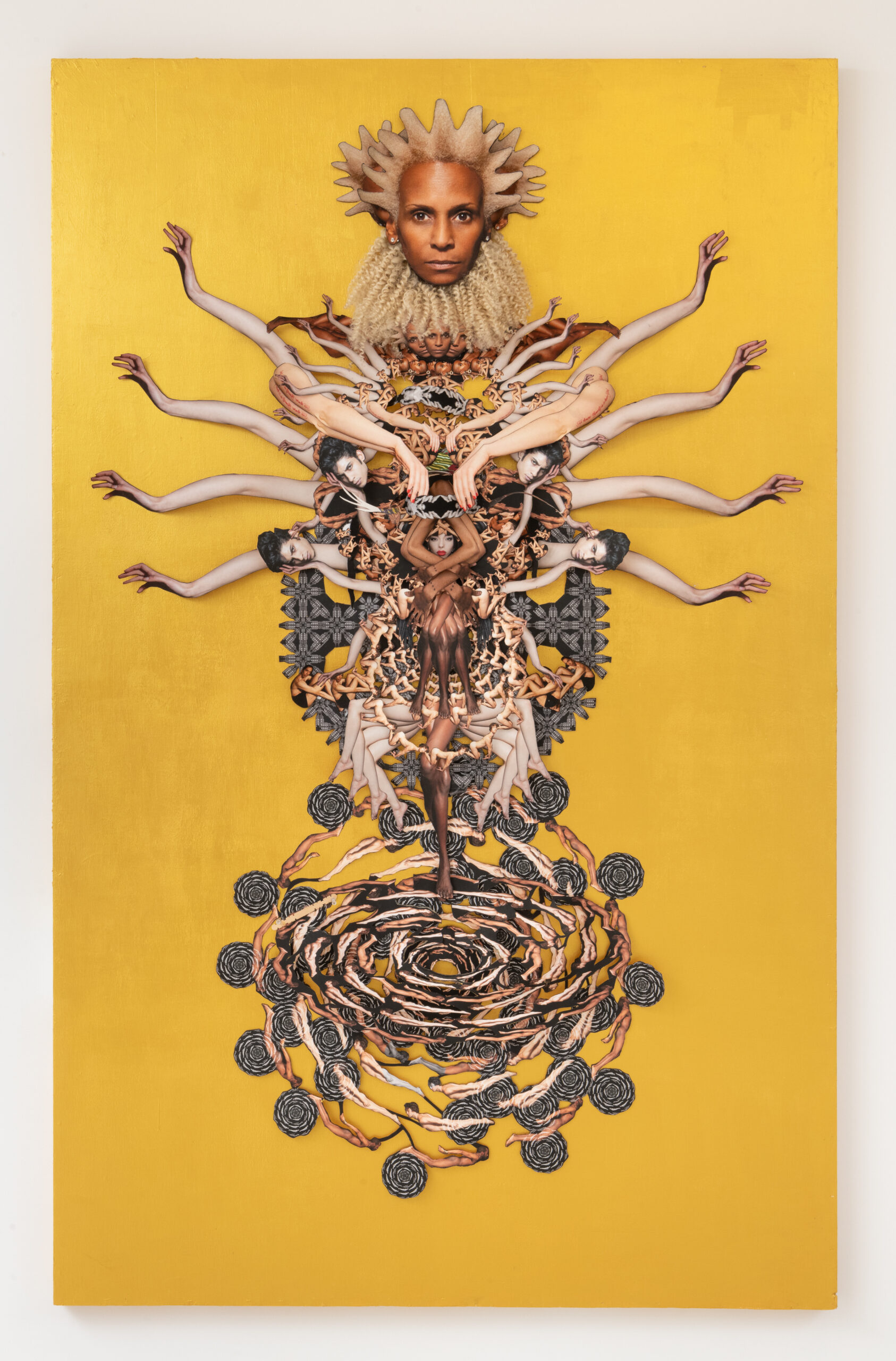

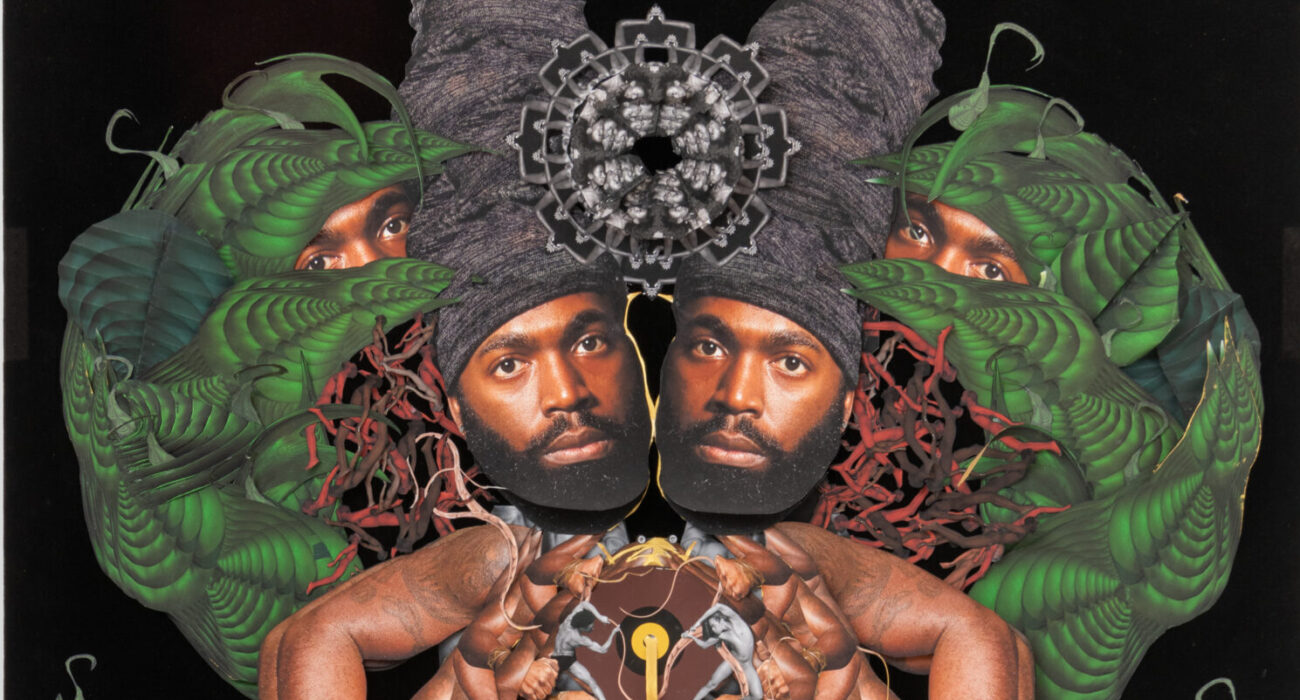

We are pleased to present an exhibition of Renee Cox’s Soul Culture, wedding analog and digital photographic technologies to facilitate a viewing experience centering joy and reflection. As a celebrated artist for the past thirty years, Renee Cox has used her background in fashion photography, graphic design (for Spike Lee, the Jungle Brothers, and Gang Starr) and modeling to forge an artistic path joining photography, conceptualism, and performance. While she focused mainly on gallery and museum exhibitions, Cox has maintained these practices, including photographing Nick Cave and Los Angeles-based Black creatives such as Lena Waithe and Melina Matsoukas, both for T Magazine. The large-scale, three-dimensional portraits emerge from Cox’s investment in fractals’ visual enchantment.

Cox’s texture and collage sensibilities merge in Soul Culture. They disclose a processional of sculptural, richly three-dimensional works combining photography and collage – waxing and waning layers bewitching the viewer. The deconstructed portraits use the human body to create fractal-like canvases, facilitating an innovative expansion of portraiture’s iconographic gestures. Paul Gilroy’s utilization of “fractal” emphasized that a seemingly chaotic and fragmented Black Atlantic functioned with fluidity and infinite possibility. This notion rests in the heart of Soul Culture’s logical and illogical naturalism with Cox’s fractal forms producing layered texture and illusionary vignettes, creating another universe and metaverse where Black folks maintain control over their representation.

Transitioning from fashion towards an art-centered career in the early 1990s, Cox inherited dual lineages from the 1970s and 1980s. Her photography is a natural progression from the Pictures Generation, including Laurie Simmons, Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger. The group employed images to confront what Douglas Eklund described as “disillusionment” with post-1960s and 1970s aspirations for change. Like Cox, they embraced mass media and interrogations of authorship by utilizing imagery from films, advertising, and replication. Cox pushed the Pictures Generation sensibilities when confronting gender’s racialized dimensions and white feminism’s limitations. Cox’s second lineage is among Black women artists such as Betye Saar, Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who have similarly meditated on racialized gender. Cox and these artists did not offer gentle, new visual imagery of Black women; instead, they shoved stereotypes and racist projections off their cliffs, looking to “conk” viewers “over the head.”

In her early practice, Cox already began centering collage in works like It Shall Be Named (1994) and Raje (1998). Solidifying her position within Afrofuturism discourse, Raje played with iconic Black women figures like actress Pam Grier and funk singer Betty Davis to craft a Black female superhero. Using her body and likeness for Raje and other works, Cox once explained, “For me, the icon comes from within; it’s very organic. It’s a reaction. I refuse to be put down, squashed, or made invisible.” Initially, Cox intended to name her character Rage; however, she wanted to avoid the project being minimized by the “angry Black woman” trope.

As an artist embracing new technologies, Cox describes, “When you’ve been working for thirty years, it’s imperative to stay current! I want my work to rule the world and have that world created by me.”

“I like to say, ‘Okay, you’re going to see this. This is going to conk you over the head when you see it. And, God forbid it should fall off the wall, it would probably kill you.’”– Renee Cox reflecting on the Bad Girls exhibition at New Museum in 1994

We are pleased to present an exhibition of Renee Cox’s Soul Culture, wedding analog and digital photographic technologies to facilitate a viewing experience centering joy and reflection. As a celebrated artist for the past thirty years, Renee Cox has used her background in fashion photography, graphic design (for Spike Lee, the Jungle Brothers, and Gang Starr) and modeling to forge an artistic path joining photography, conceptualism, and performance. While she focused mainly on gallery and museum exhibitions, Cox has maintained these practices, including photographing Nick Cave and Los Angeles-based Black creatives such as Lena Waithe and Melina Matsoukas, both for T Magazine. The large-scale, three-dimensional portraits emerge from Cox’s investment in fractals’ visual enchantment.

Cox’s texture and collage sensibilities merge in Soul Culture. They disclose a processional of sculptural, richly three-dimensional works combining photography and collage – waxing and waning layers bewitching the viewer. The deconstructed portraits use the human body to create fractal-like canvases, facilitating an innovative expansion of portraiture’s iconographic gestures. Paul Gilroy’s utilization of “fractal” emphasized that a seemingly chaotic and fragmented Black Atlantic functioned with fluidity and infinite possibility. This notion rests in the heart of Soul Culture’s logical and illogical naturalism with Cox’s fractal forms producing layered texture and illusionary vignettes, creating another universe and metaverse where Black folks maintain control over their representation.

Transitioning from fashion towards an art-centered career in the early 1990s, Cox inherited dual lineages from the 1970s and 1980s. Her photography is a natural progression from the Pictures Generation, including Laurie Simmons, Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger. The group employed images to confront what Douglas Eklund described as “disillusionment” with post-1960s and 1970s aspirations for change. Like Cox, they embraced mass media and interrogations of authorship by utilizing imagery from films, advertising, and replication. Cox pushed the Pictures Generation sensibilities when confronting gender’s racialized dimensions and white feminism’s limitations. Cox’s second lineage is among Black women artists such as Betye Saar, Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who have similarly meditated on racialized gender. Cox and these artists did not offer gentle, new visual imagery of Black women; instead, they shoved stereotypes and racist projections off their cliffs, looking to “conk” viewers “over the head.”

In her early practice, Cox already began centering collage in works like It Shall Be Named (1994) and Raje (1998). Solidifying her position within Afrofuturism discourse, Raje played with iconic Black women figures like actress Pam Grier and funk singer Betty Davis to craft a Black female superhero. Using her body and likeness for Raje and other works, Cox once explained, “For me, the icon comes from within; it’s very organic. It’s a reaction. I refuse to be put down, squashed, or made invisible.” Initially, Cox intended to name her character Rage; however, she wanted to avoid the project being minimized by the “angry Black woman” trope.

As an artist embracing new technologies, Cox describes, “When you’ve been working for thirty years, it’s imperative to stay current! I want my work to rule the world and have that world created by me.”